“Shakespeare, Rembrandt, Beethoven fera des films…toutes les légendes, toutes les mythologies et tous les mythes, tous les fondateurs de la religion, et les religions mêmes…attendent leur résurrection exposée, et les héros s’entassent à la porte.”

(“Shakespeare, Rembrandt, Beethoven will make films …all legends, all mythologies and all myths, all the founders of religion, and even the religions … await their resurrection, and the heroes at the gate.”)

-Abel Gance

This post is in part a follow-up on my earlier entry on Waterloo where I repined the lack of cinematic attention paid to The Napoleonic Wars. Here I’ll make an attempt to describe what was the most exhausting, challenging, at times frustrating, but ultimately engrossing and rewarding moviegoing experience of my life. As discussed in my last entry, my main reason for coming to London was to attend the Cinema and Memory Conference, however an added bonus was that the week of the conference also coincided with the wide release of the latest restored version of Abel Gance’s landmark epic film Napoleon (1927). In November 2016 Academy Award-winning film historian Kevin Brownlow and the British Film Institute (BFI) National Archive unveiled a new digitally restored version of Abel Gance’s cinematic triumph. Aside from playing at cinemas across the U.K. with an orchestral accompaniment of Carl Davis’s awe-inspiring score when the film was also made available on BFI DVD/Blu-ray and BFI Player. If you want just the slightest taste of the power and majesty of this restoration take a look at the trailer below:

The premiere took place earlier that month at the Royal Festival Hall, where Davis’ score was accompanied by a performance by the Philharmonia Orchestra. Unfortunately I missed both the initial premiere and a special retrospective held by none other than Kevin Brownlow at the BFI earlier in the week. Before I describe my own experience watching this jaw-dropping exhibition, it is only fitting to share at least in part, the incredible story surrounding Brownlow’s fifty year long journey to bring this silent classic back to life. Brownlow recounts the full scope of his story in a 2013 interview in The Guardian. Here he recalls the moment over sixty years ago in which he first encountered the film that would go on to change and ultimately shape his life.

It was 1953 and I was still at school. I’d borrowed a silent French film from the library for my 9.5mm projector. It was by Jean Epstein and it was awful. So I rang the library and asked if they had anything else. They said they had Napoleon Bonaparte and the French Revolution. “Oh that will just be a classroom film,” I said, “full of engravings and titles and all very static…But when it arrived, we played it on the wall and I’d never seen anything like it. This, I thought, is what cinema ought to be. I realised what I had was two reels of a six-reel version put out for home cinema use. So I started advertising in Exchange and Mart until I got the rest of it. And then people started coming to see it.”

However even after Brownlow got a hold of the six reel version of the film, he learned that he had acquired just the tip of a five-and-half-hour long iceberg. Brownlow was so inspired by the beauty of the fragments he had seen that he reached out to the film’s director Abel Gance to learn about the whereabouts of the rest of the film. Made just at the end of the silent film era, it was hailed as a masterpiece but dismissed by exhibitors as too long, and too impractical to be shown to mass audiences. (Gance’s definitive cut which was only exhibited a handful of times in the Spring of 1927 ran close to nine and a half hours.)

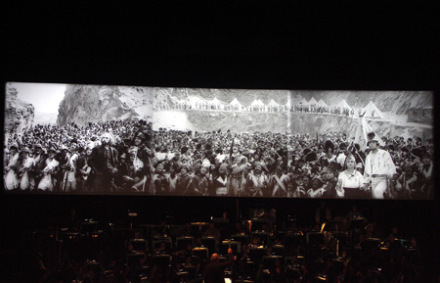

The film was eventually cut down into shorter versions which ran anywhere between ninety minutes and four hours, but because of the butchering entire scenes disappeared and were presumed to be lost and by the time Brownlow discovered Napoleon in the 1950s, only fragments of the film remained. More tragic is the fact that the film does not cover the entirety of Napoleon’s life, but instead takes viewers from his early life up until 1796 and ends with the decisive Battle of Montenotte. After nearly ninety years of experimentation, the film’s famous “triptych sequence” was carried out in all of its intended glory at the BFI screening I attended. The climatic battle scene involves the simultaneous projection of three reels of silent film arrayed in a horizontal row, making for a total aspect ratio of 4:1 (3× 1.33:1). Gance worried that the film’s finale would not have the proper impact by being confined to a small screen, and thought of expanding the frame by using three cameras next to each other. This is probably the most famous of the film’s several innovative techniques. Though American filmmakers began experimenting with 70mm widescreen (such as Fox Grandeur) in 1929, widescreen did not take off until CinemaScope was introduced in 1953.

The method Gance developed was coined “Polyvision” by critics and was only used for the final reel of Napoleon, to create a climactic finale. Filming the whole story in Polyvision was logistically difficult as Gance wished for a number of innovative shots, each requiring greater flexibility than was allowed by three interlocked cameras. When the film was greatly trimmed by the distributors early on during exhibition, the new version only retained the center strip in order to allow projection in standard single-projector cinemas. Gance was unable to eliminate the problem of the two seams dividing the three panels of film as shown on screen, so he avoided the problem by putting three completely different shots together in some of the Polyvision scenes. When Gance viewed Cinerama for the first time in 1955, he noticed that the widescreen image was still not seamless, that the problem was not entirely fixed.

After two decades of restoration work and a practice of cinematic archeology on a scale only matched by the boldest treasure hunters, Brownlow’s collaboration with Gance unveiled a five hour 35mm ‘definitive version’ of the film at the Telluride Film Festival in 1979. Gance at just a month shy of turning ninety, made the journey to Colorado to and watched the film from his hotel window. Despite his limited mobility, it is said that he rose and stood through the entire final reel with the restored ‘triptych sequence.’ Despite the lack of music and the piercing cold of the outdoor screening, the event is a revelation for its audience. Francis Ford Coppola provided his own butchered re-edit of Napoleon the following year and the story goes that Brownlow was so horrified at his edit that he compared Coppola to Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels.

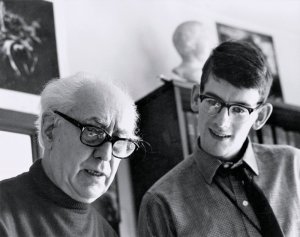

In the four decades that followed the 1979 Telluride “premiere”, Brownlow has continued his groundbreaking efforts as a film historian and preservationist. His passion and love for silent cinema is truly infectious, as well his ongoing pursuit make aware the truly dynamic and immersive aspects that silent specatorship entailed. In 2010 his efforts were rewarded with a honorary Academy Award. I came across his acceptance speech online several years ago while I was fumbling around for a research specialty early in graduate career. You can see his entire acceptance speech below, it is truly inspiring and in many ways helped to give me a sense of direction and purpose as to why this period of film history is so significant and necessary to be restored and reinvigorated.

As for the experience of watching Napoleon in a theater, which included an accompanying orchestra and pull out screen to display the entire triptych sequence, it was something on par with seeing a natural wonder. In an earlier post I described how the experience of the Mona Lisa smile is something that can only be made possible when you put the selfie stick down, push through the crowd, walk up to the painting and allow yourself to concentrate. A theatrical screening of Gance and Brownlow’s (by this point it truly has become both men’s film) Napoleon requires no such level of concentration. The forcefulness of Davis’ revised score, the striking visual imagery, and all around atmosphere of being surrounded by only the most committed and passionate of silent film buffs, is entirely absorbing. I won’t go as far to say that the five and a half hours flew by, the film’s length is readily apparent, and I certainly was grateful for the occasional breaks given, but similar to a daylong Netflix binge-watch session, I was compelled to want to delve further into the story and see what happens next. This type of serious moviegoing is not for the faint of heart, and I would say that by the end of the screening nearly half of the audience had bowed out and left. Similar to running a marathon, or century bicycle ride, this movie requires stamina and more definitive commitment. I can’t go as far as to recommend that everyone sit through and engage with this film in its entirety, it is quite taxing, however to even take in a few of the sequences and experience at least a piece of this masterpiece is a truly trans-formative experience. It seems as if the BFI understands this aspect of viewership and provides would-be viewers a very useful list of can’t miss scenes.

The tragedy of Napoleon is in the fact that Gance had intended to create further installments of his film, which would have carried Napoleon’s epic story all the way through to Waterloo and his last days on St. Helena. The name Waterloo has since become a word synonymous with the idea of an individual meeting his or her ultimate obstacle and to ultimately be defeated by it. I say this with all irony intended that Abel Gance met his Waterloo with Napoleon. However after seeing his ending triptych sequence in all its cinematic splendor, I can’t help but think of the 360 degree film Waterloo XXL that I watched at Memorial 1815 in Belgium, and imagine if it could perhaps be considered the final completion of Gance’s unfulfilled ambitious vision. On the other hand the film’s staying power and the success of Brownlow’s restoration is nothing less than a triumph. It is a message to the world of the power and influence that the film industry’s silent past continues to wield, along with the tireless efforts of preservationists and historians who continue to work to give it a voice.